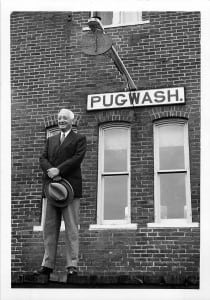

Cyrus Eaton (1883-1979) was born just outside of Pugwash, Nova Scotia, at Pugwash Junction. He was raised there, in a deeply religious family, and later attended McMaster University, initially intending to become a Baptist minister. Summer jobs working for John D. Rockefeller in Cleveland, Ohio, however, introduced him to the world of capitalism, and after a year as a lay minister near Cleveland, he decided to follow the advice and career path of his famous mentor. Beginning with his first company in Brandon, Manitoba, he built a phenomenally successful utilities empire in the Canadian and American Midwest. A millionaire by 1910, he became an American citizen in 1913. His fortune continued to grow, and he joined the ranks of America’s most successful business tycoons and captains of industry. Losing his business empire in the Great Depression, he rebuilt an even greater fortune a second time, with enterprises in iron ore mining, railroads, steel manufacturing, rubber and paint industries, venture capital financing, and cattle.

Cyrus Eaton (1883-1979) was born just outside of Pugwash, Nova Scotia, at Pugwash Junction. He was raised there, in a deeply religious family, and later attended McMaster University, initially intending to become a Baptist minister. Summer jobs working for John D. Rockefeller in Cleveland, Ohio, however, introduced him to the world of capitalism, and after a year as a lay minister near Cleveland, he decided to follow the advice and career path of his famous mentor. Beginning with his first company in Brandon, Manitoba, he built a phenomenally successful utilities empire in the Canadian and American Midwest. A millionaire by 1910, he became an American citizen in 1913. His fortune continued to grow, and he joined the ranks of America’s most successful business tycoons and captains of industry. Losing his business empire in the Great Depression, he rebuilt an even greater fortune a second time, with enterprises in iron ore mining, railroads, steel manufacturing, rubber and paint industries, venture capital financing, and cattle.

» Learn more about Cyrus Eaton in Mel James’ biography (PDF)

With his entry into the world of high finance and capitalism, Eaton’s desire to better the world, still intact, found expression in secular channels rather than through religion. Convinced of the important connection between education and social improvement, he became a major benefactor of many institutions of higher learning, including Université Laval, McMaster University and Acadia University. He also supported several American colleges and universities, in particular the University of Chicago, on whose board he served for decades as a trustee. In his personal life he preferred a quiet life of reading and reflection to a conspicuous display of his wealth; particularly interested in philosophy and poetry, and attracted by the humanist approach of rationalist thinkers, he took seriously the goal of personal intellectual improvement.

Eaton also never forgot his home province of Nova Scotia, where he returned to spend his summers. By the 1920s, Pugwash, the village of his youth, had fallen on hard times: its shipbuilding industry had declined, leading to economic depression, and the village had been devastated by fires. Eaton resolved to invest in its revival and beautification. He purchased Thinkers’ Lodge — then called Pineo Lodge — and refurbished and opened it as a summer inn, run by his sister, with the goal of revitalizing the village’s economy. He built a state-of-the-art school nearby, hiring a leading American architect to design a beautifully proportioned brick building in the Greek Revival style. He also financed and helped establish the Pugwash Park Commission, incorporated by act of the Provincial Legislature in 1929.

Eaton also never forgot his home province of Nova Scotia, where he returned to spend his summers. By the 1920s, Pugwash, the village of his youth, had fallen on hard times: its shipbuilding industry had declined, leading to economic depression, and the village had been devastated by fires. Eaton resolved to invest in its revival and beautification. He purchased Thinkers’ Lodge — then called Pineo Lodge — and refurbished and opened it as a summer inn, run by his sister, with the goal of revitalizing the village’s economy. He built a state-of-the-art school nearby, hiring a leading American architect to design a beautifully proportioned brick building in the Greek Revival style. He also financed and helped establish the Pugwash Park Commission, incorporated by act of the Provincial Legislature in 1929.

In 1920s North America, the word “park” suggested not only natural parkland, important for moral uplift, but also a modern and efficient setting for economic and industrial activity. With Eaton as Chairman, the three-member Commission undertook the establishment and maintenance of a waterfront park in Pugwash, where previously only decrepit or burned warehouses had stood, as well as overseeing the running of the Lodge.

Not only an astute and successful businessman, Cyrus Eaton was also a visionary philanthropist. Included in the founding mission of the Pugwash Park Commission was the “establishment and maintenance of places where educators, scientists and scholars can meet for educational, scientific and literary discussions and for the exchange of ideas on educational, scientific and literary subjects and generally for the advancement and improvement of learning and education.” Eaton saw the isolated village of Pugwash as an ideal location for retreats for people from many walks of life to escape the pressures of their everyday work life, to relax and to refocus. In the 1950s, with the Lodge losing money as a tourist destination, Eaton began organizing and financing such gatherings. Initial meetings brought together local officials from Nova Scotia to discuss topics ranging from rural schools to the education of police officers.

» Atomic Age Powwow in Pugwash, Life Magazine 1957 article

Eaton soon took on more ambitious questions. In 1955 he hosted a conference of university presidents and professors from Canada, the United States, and Great Britain, including British biologist and philosopher Sir Julian Huxley. Discussions focused on the need to use the “possibilities of fission and fusion” for peace and not for war. At the end of the retreat, the participants presented Eaton with a scroll that included the following message: “It was your inspiration to bring together in fruitful communion men and women of the most diverse attainment, men of action and men of thought, writers, businessmen and scholars. We may well have witnessed the birth of one of those ideas destined to open up ever-increasing possibilities of good.”

The following year, representatives from 11 countries met to discuss the problems of the Middle East, in particular the Suez situation. In addition to guests from China, Iraq, Israel and the United States, among others, the meeting was attended by Alexander M. Samarin, a member of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. Dr. H.N. Fieldhouse, dean of arts and sciences at McGill University, who served as moderator, later commented: “Nobody who has taken part, however briefly, in Mr. Eaton’s experiment can have any doubts about its value. None of us can talk today about Middle Eastern affairs in quite the same way we would have done before we met.”

The inclusion of a representative from the Soviet Union reflected Eaton’s growing convictions about the folly of the Cold War. A convinced and committed capitalist, Eaton nonetheless rejected the rigid and confrontational assumptions of Cold War thinking, advocating instead dialogue and understanding between East and West. The rustic and peaceful setting of Pugwash, Eaton hoped, could provide an atmosphere conducive to fruitful discussions and exchanges on such fundamental questions.

» View a Chronicle-Herald article from July 1960 about Cyrus Eaton winning the Lenin Peace Prize

In September 1957, a Cleveland newspaper reported on an “unusual holiday of combined intellectual stimulation and physical relaxation in the placid surroundings of a little Nova Scotia fishing village.” One group of college presidents and another of deans and their wives had been guests of Cyrus Eaton, taking a holiday “from the wearying problems of administration, fundraising, faculty salaries and enrolments” to refresh their appreciation of great books and reflect on the aims of education. The newspaper noted that “Eaton’s home … has become renowned in three years for the ‘Thinkers’ Sessions’ that have drawn great minds of many nations together to ponder problems of the world.” Indeed, it was around this time that Pineo Lodge started to be called by a new name: Thinkers’ Lodge.